In Berber Country

“Please, stop the car,” I asked Hussain, my good-natured petit taxi driver.

We had been driving through Casablanca’s wide boulevards and avenues for the last half hour and I needed some air. Hussain pulled over at a traffic-choked street. I climbed out and caught my breath. The air smelled of exhaust. A row of boxy gray buildings shadowed over me. Drivers yelled at each other and honked their car horns tirelessly, as if their life had depended on it. I took another breath. This was not the Morocco I had been dreaming about. Where were the souks and the belly dancers, the sheiks and Aladdin’s lamp? I had come here looking for the worlds of Humphrey Bogart. Instead I found in Casablanca a spread out commercial hub.

“Can you show me the city?” I had asked Hussain earlier that day. “Tourists do not usually stop here,” he had replied, slightly bemused. Still I had insisted.

Hussain got out of the car and motioned me toward a meloui flatbread vendor. After a short exchange between Hussain and the vendor, a warm piece of delicious fluffy dough topped with a dollop of honey was in my hand. We ate standing up as motorbikes raced past. “Now,” Hussain said, “we will visit our famous mosque.”

We drove to Hassan II Mosque, a formidable structure jutting into the Atlantic Ocean. The vast square surrounding the mosque was quiet, save for the restless seagulls. A towering minaret rose against the pale blue sky. A few men clad in pointy djellabas passed by me, gliding across marbled floors of the square with patterned mosaic tiles. While Hussain waited for me in his car, I stood on the edge of the city and tried to overcome a sense of disillusion that was quickly settling in.

I hadn’t always been this way.

An avid traveler, I had approached new places with humility, openness, and as few expectations as possible. But I had been dreaming of Morocco for such a long time that its reality was bound to disappoint me.

Days after the Casablanca encounter I met Ismail, a local guide, in the imperial city of Fez. Fez came closest to my ‘imagined’ Morocco. I spent hours in its crowded souks, dodging donkeys hauling supplies to the old-as-earth Chouwara leather tannery through narrow cobblestone streets. Ismail, a dark-haired man with inquisitive eyes and a kind disposition, picked me up from my quiet riad. "Smell this," he gave me a mint twig just as the stench of dead flesh from the tannery was taking over my nostrils.

Our desert adventure has thus begun.

On the road, the snow-capped Middle Atlas mountains, barely visible earlier, fully came into view.

Here and there, they split into wide poppy fields and dirt tracks that stretched toward the horizon. As our battered van pushed ahead, the Berber identity of Morocco slowly began to unfold.

Ismail was a Berber, a proud one. Over a cup of strong mint tea at a roadside cafe in Ifrane, he told me that nomadic Berber tribes had inhabited northern Africa well before Arabs took over in the eighth century. In present day Morocco, the Berbers still represented ethnic – although not political – majority.

Halfway between Fez and Sahara the lush Middle Atlas gave way first to high plains, then to the drier High Atlas. The green fields around us slowly rolled into brown and red plateaus. The desert’s presence grew with each kilometer.

So did my Berber knowledge.

“ Three things define us. Freedom. Hospitality. Dignity. But the greatest of these is freedom.”

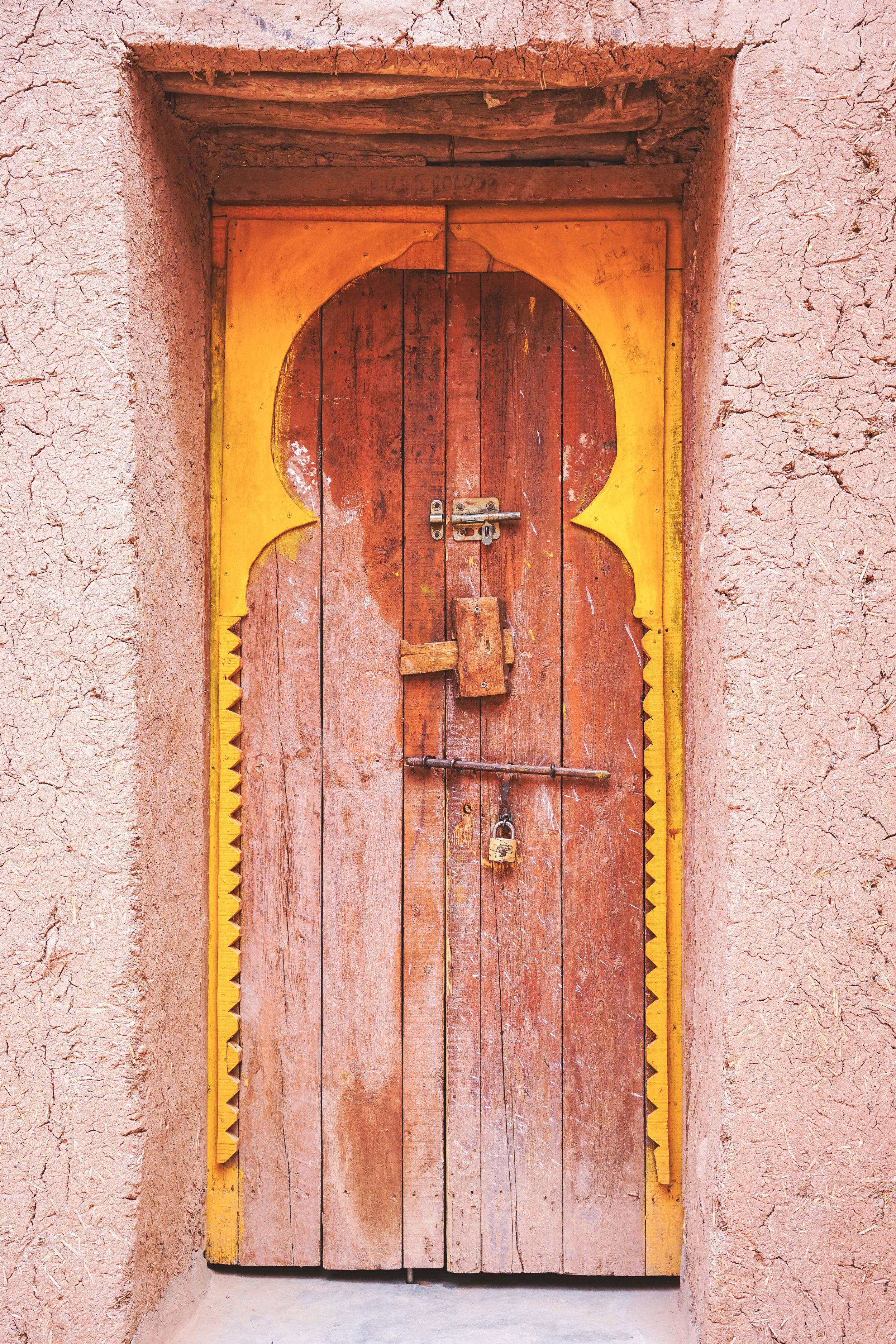

“Three things define us,” Ismail told me in Aït Benhaddou, an old ksar along an ancient caravan route from the Saharan sands to Marrakech.

“Freedom. Hospitality. Dignity.” I had asked him earlier about ⵣ, a peculiar sign I had spotted on mud house walls and boulders everywhere. It was the sign of the Berber: Amazigh, the free man. “But the greatest of these,” continued Ismail, “is freedom. A Berber nomad lives freely in the desert and in the mountains. It is innate to who we are.”

Berber romanticism was seductive.

The original nomads, as I called them, used to roam the lands of North Africa, free to go as they wished. Although mostly settled now and living a farming lifestyle, the Berbers I had encountered on the way to Sahara still stood tall with a vagrant gleam in their eyes.

We were approaching the desert and the Arabic influence, palpable earlier, was decreasing. A Tuareg desert blues band, Tinariwen, sang love songs to Tenere, the desert, from the van’s stereo. The desert, it seemed, was not just a land here. “We’re coming home to our mother,” Ismail said when the first golden dunes appeared on the horizon.

Berber tribes have been scattered across North Africa, from Mauritania in the East to Egypt in the West. Although islamized, they have maintained their roots over the centuries of Arab rule. In recent years, there has been an awakening, a Berber Spring of sorts. Different social dynamics across the Berber-populated countries have hindered the efforts, but there is hope in Morocco. According to Ismail, the Berbers here are less isolated than their counterparts in other areas. The current king, part Berber, seems to be open to the cause. There are signs that the country is changing, slowly. Berber language, Tamazight, has become Morocco’s official language in 2011.

Still there was more work to do.

We arrived at Merzouga, the last pre-Saharan outpost, just as the air turned notably arid. A crew of barefoot children, smiling and screaming, followed our slow-moving van. Largely illiterate, these kids would have few opportunities to better their lives if it were not for educational charities working in these remote areas.

At home in the US some weeks later, I could not shake off proud Berbers from my imagination.

I thought of the famed fourteenth century Moroccan explorer of Berber descent, Ibn Battuta, and the modern day Rotterdam mayor, Ahmed Aboutaleb, a Riffian Berber. Scrolling through Instagram one day, I stumbled upon a profile of Abdela Igmirien and learned that he, too, was a Berber.

It was then that I stopped calling the Berbers by their Western name. “We prefer to be called Imazighen (Amazigh in its singular form),” Abdela told me. “The term Berber ("barbarian") comes from the Greeks and the Romans who used to put everyone who did not speak Latin into this faceless group.”

Perhaps I was the barbarian all along.

ⵣ

Yulia is the founder of NOMⴷD + JULES and a freelance travel photographer and writer. She was born in Kazakhstan, grew up in Estonia, and now lives in the United States. Yulia has traveled the world extensively and turned to a travel journalism career after spending more than ten years in large organizations - first as a Navy Sailor, then as a brand manager at Fortune 500 companies. Yulia's work appears in Lonely Planet, Afar magazine, Turkish Airlines Skylife, and others. See more on her Website and Instagram.